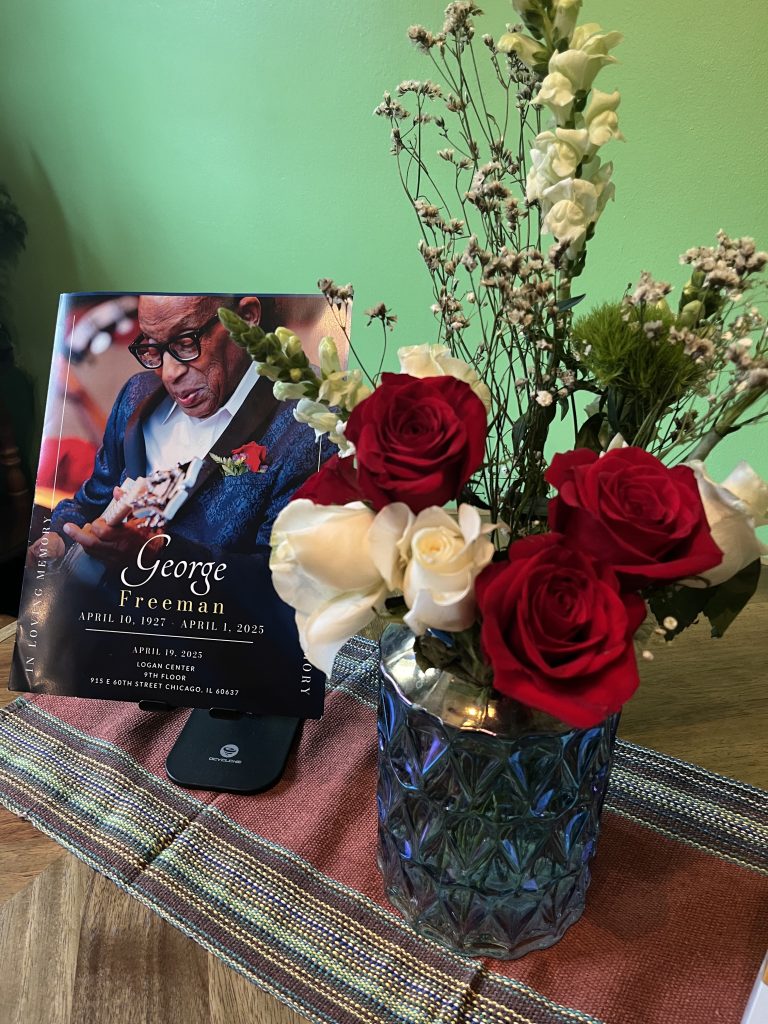

On April 19, 2025, George Freeman’s memorial was held at the University of Chicago’s Logan Center. Below are the remarks I delivered in dedication to the the remarkable life of my friend and mentor George Freeman (April 10, 1927–April 1, 2025). The memorial was a remarkable event. The community came together at his memorial to express pure love for this man. Thanks to all who made this event so special.

It was the fall of 1991. Jon Logan, Von Freeman’s pianist at the New Apartment Lounge, invited this young guitarist to come sit in at the Bei Jee Man’s Lounge, just east of 71st and King Dr. I was obsessed with Von’s solo flights, but Jon suggested that I also hear George Freeman. So it was on a Thursday that I met George. He intrigued me by his musicianship—masterful use of space, ripping lines, the strongest swing I had ever heard on guitar, adroit melodies, and unorthodox sonic worlds, often in the same solo and with a giant pick. After the set, when Jon introduced me to George, George grabbed my picking hand with such force I thought he was going to break it. He looked me right in the eye said, “how the hell are you, young man.” I would subsequently go see him over the next few years. However, after joining Von in 1997, I seldom saw George.

15 years later, in 2012, at Von’s memorial, George and I spoke for the first time in several years. A year later, in July of 2013, drummer Mike Reed asked if I would like to start a group with George to play a month of Thursdays at his new club Constellation. His reasoning was that it would be special to bring Von’s guitarist together with Von’s guitarist brother. This collaboration might also help me with my PhD research about to start that fall at the University of Chicago. I called George, he was into it, and we started our collaboration with Pete Benson and drummer Mike Schlick. Over this first month, I was struck at how effortlessly he and I made music together.

From there, it then became a regular occasion for us—I would come over once a week and we would jam on standards and his originals. His memory was sharp. He would remember tunes he composed that he hadn’t thought of in years. During these meetings, he would also tell stories about Charlie Parker, Henry Pryor, Johnny Griffin, family, friends, and his adventures on the road. I would sit enthralled with each story. He spoke in detail about people, attire, equipment, venues, his feelings. In these stories he theorized about music and art—how he learned to use the blues in his playing and why it’s important, his rhythmic principles, how he developed alternate picking, and much more. When we played, instead of each of us playing a solo and ending the tune, we would trade chorus after chorus for hours without saying a word.

Eventually George helped me develop the foundation of my dissertation research. So, when I started to think about how the urban landscape shapes culture, George came up with the idea of driving around the South Side so he could point out places in which he used to perform. The stories that rolled out of him both confirmed and challenged common narratives about jazz and Chicago. Through his stories, he contributed to knowledge about clubs like the Rhumboogie, the Pershing Hotel, and The Toast of Town; characters like Cadillac Bob and promoter McKie Fitzhugh; and he brought to light the important work of Dr. Mildred Bryant Jones. It was she who founded and directed DuSable High School’s music program in 1935, not Captain Dyett. Since 1920 she had taught music theory, composition, vocal arts, and piano at Wendell Phillips and hired Dyett in 1931. George disclosed that it was from Dr. Bryant Jones that Von learned music theory and composition. If it wasn’t for George, we might not know about this important woman’s substantial contributions.

We had innumerable other experiences together: 12 years playing an annual birthday bash with Bernard Purdie and Pete Benson at the Green Mill; we played in Poznan, Poland, which, thanks to Lauren Deutsch, was his first time performing in Europe; he spoke in several of my UChicago World Music and jazz courses; we worked several concerts and residencies with his nephew Chico; we celebrated his 90th birthday at the Chicago Jazz Festival; I would take him to Walgreens to help him get medications and other supplies; we took his guitars to get fixed. We released a live album. After I earned my PhD in 2020, he would call me the “doctor” and would ask “are you making house calls”? And through all this, he made each experience deeply meaningful through his sense of humor (“did the doctor bring my medicine?”).

Sitting on stage with him, I was always impressed how without fail he would connect with an audience. From watching him, I learned how to pace, take time, and use the guitar to reach people in the deepest manner. Indeed, the one thing that made our relationship something deeper in my mind was the guitar. I not only heard what he played; I could see it. More than that, I saw guitar history in front of me every time we played—the way he navigated the fretboard, how he used the tone knobs or his pick to get different sounds to enhance the expressive qualities of his music. There was deep science behind the music of both Freeman brothers that I served under, but I could witness that science through George’s guitar playing.

During George’s last days, I visited almost daily to talk to him and play guitar for him. One day he got excited when I played “These Foolish Things”. He told me “I love it—the bridge isn’t right.” One day, as he seemed to be sleeping, he looked at me suddenly and asked, “how the hell are you, doctor?” This moment reminded me that for his whole life George was consistently George. George was someone who lived his truth and fought to bring it to the world with courage, joy, and pure artistry; a man of deep generosity who was invariably willing to enter into conversation and fellowship with anyone. I not only saw the fruits of his labor through our performances, and through his joyful interactions with others, but also in his family. Witnessing Mark and Sierra’s love for Uncle George, the way they both cared for him daily, particularly as he transitioned, showed me a dedicated family love that is profound and inspiring, made even stronger through music.

Von once said about music, “you see, your emotions are involved here, so that adds something that’s really infinite, and I think that’s the reason why so many musicians do not live up to their potential, because if they do, then the listeners will know where they are. Your weak points as well as your strong points are involved. Now, if you’re really playing a ballad, you’ve gotten past tone, past chords, and you’re over into emotional sounds and you’re exposed.” I hear George in this description. Through his kindness and seriousness, George lived and played beyond his potential. And, he drew others’ potential out of them. His courage was demonstrated when he exposed his vulnerability in art or among family and friends. You always knew where George was—he was with you, honestly, joyfully, purely George Freeman.

George, thank you for the gifts you shared with all of us, through your playfulness, your music, and your guitar. The doctor will do his best to keep yours and Von’s flames burning. And please know: you’ll always be with me—in both heart and sound.